Women in the Workplace – Working Hard for the Money

Wrapping up our series on Gender Inequality and Corruption in Kosovo, in Part V we are going to move on from participation rates and look at unemployment rates, as well as the types of jobs women are being employed in.

Unemployment Rates

According to the 2014 Kosovo Labour Force Survey, the unemployment rate for women in Kosovo was 41.6%. Although very high, the unemployment rate for women has actually fallen significantly over the past 10 years. As recently as 2008 the unemployment rate was 59.6%, and going back to 2002 it was 74.5%.

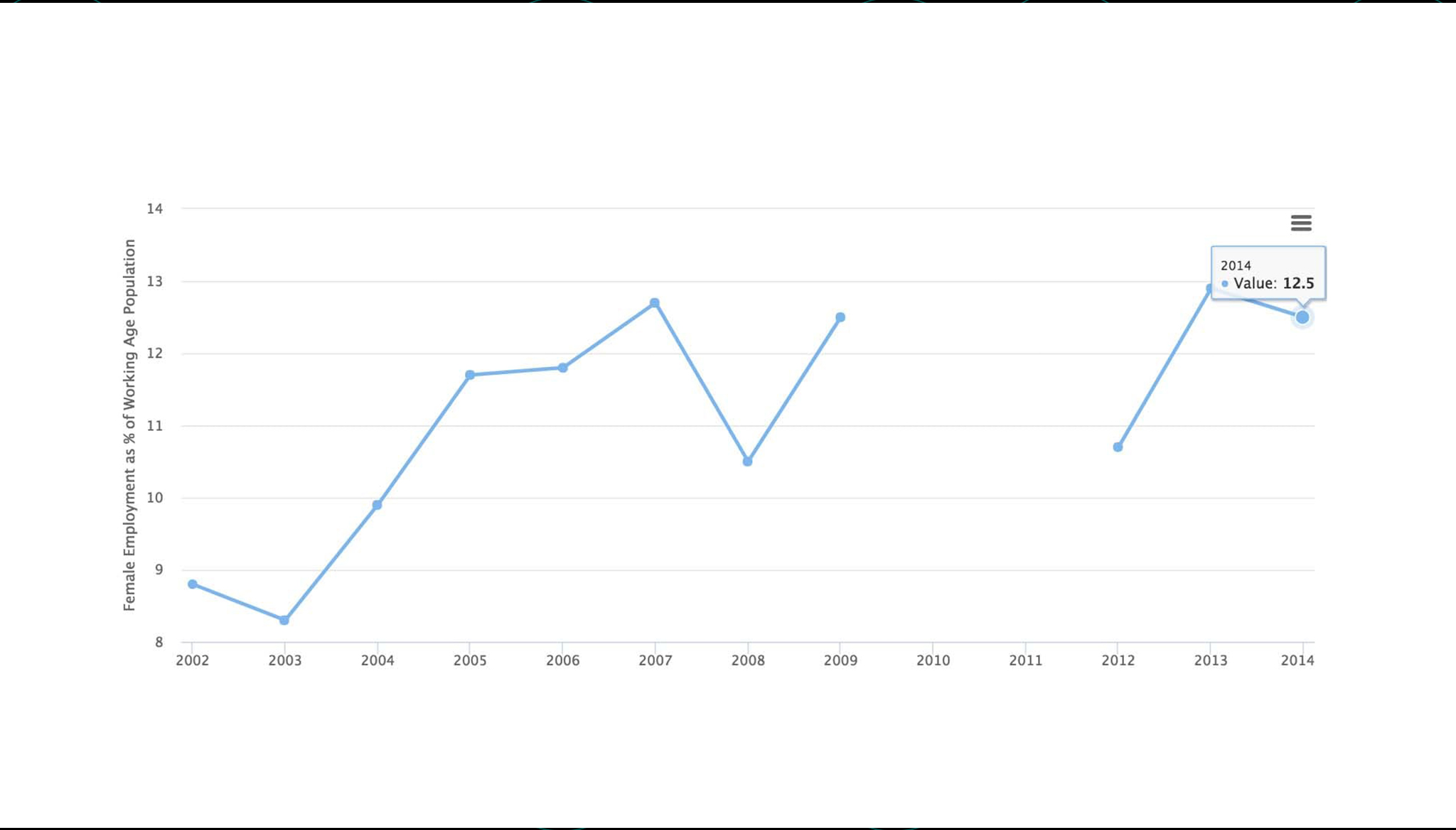

So, over the past decade, Kosovo has seen falling unemployment rates for women but, as covered in Part IV, also a falling participation rate (see Chart 1). The question is: what is the net impact? Are more women getting employed, or are they simply not entering the labour force at all?

Chart 1 – Participation Rates 2002 to 2014

Looking at the data on employed women as a percentage of the total working age population of women (see Chart 2), there has been essentially no increase in the percentage of women being employed since 2005. This means that the reduction in the unemployment rate for women since 2005 has been a result of less women entering (or staying in) the labour force, rather than any increase in employment.

Unemployment by Age

Although unemployment for women overall is high, there are also significant differences in unemployment rates when broken down into different age brackets.

The overall trend of decreasing unemployment as age increases is not something that is unique to Kosovo. According to the World Development Indicators, across the world from 2010 to 2013, the unemployment rate for men aged 15-24 was 7 percentage points higher than for the population as a whole. For women, the corresponding differential was 10 percentage points.

Nevertheless the magnitude of the youth unemployment rate for women, at over 70% for those aged between 15 and 24, is alarming. These are women actively seeking work. As age progresses, we do see the unemployment rate drop for both men and women, but then something interesting happens. From age 45 onwards, the unemployment rate for men overtakes the rate for women. There are at least two contributing factors to this.

The first is that, women are still primarily seen as having non‑work related responsibilities in Kosovo. This implies that many women who are employed are working to provide a second source of income for their family, or because they don’t have enough family related responsibilities to keep them busy full time. When someone in that position finds themselves unemployed, they are unlikely to persist in their search for a job, and instead drop out of the labour force altogether. If that person was a primary breadwinner for their family, as men seem to generally be in Kosovo (based on the data), the motivation to stay in the labour force and continue looking for work is much stronger.

The second reason relates to the type of employment that men and women typically take. As we will see in more detail in the following section, men are more likely to take unskilled positions and positions requiring physical labour. This means that, as they age, they are easier to replace with younger unskilled workers. Having only a specific skill set developed in a certain type of job, these men are likely to have more difficulty finding other sources of employment.

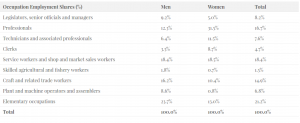

Looking at the breakdown by occupation type provided in the 2014 Kosovo Labour Force Surve (see Table 1), the data indicates that the types of jobs men and women take tend to be very different. For those women who are employed, they are more likely to be in professional positions (31.5% of women vs. 12.3% of men) or technicians and associated professionals (11.5% vs. 6.4%). Meanwhile men are more likely to be in “elementary occupations”.

Table 1 – Employed Persons by Occupation Type

Looking across the other categories, there is also a significant discrepancy between men and women employed as legislators, senior officials and managers. 9.2% of employed men are in one of these positions versus 5.0% of women, which translates to only 14.2% of these positions being held by women. In a workforce where women represent 23.2% of all employees, this means women are significantly underrepresented in these senior positions.

The biggest employer of women in Kosovo was the government (including the public service and the army) with 42.7% of all employed women in 2013. Although it was the biggest employer of women, it was also a substantial employer of men, employing 28.0% of the market. As a result, women still only made up 30.3% of total employees in the government sector. It should be noted that this means women are overrepresented in these positions when compared to the overall employment market. For the full breakdown by employer type, please refer to this sunburst chart.

In terms of industry, the two largest employers of women in the Kosovar economy in 2014 were the ‘Education’ or ‘Human health and social work activities’ sectors. 39.2% of employed women worked in one of these sectors. In fact, the ‘Human health and social work activities’ sector was the only sector that employed more women than men.

Overall, the breakdown of where women worked, and the types of positions they held in Kosovo is not unusual. Many countries, in both the high and low income countries, see concentrations of women working in education, health and social services related fields. Many of these countries also see women typically taking more professional and technical roles, as opposed to low skilled and/or roles requiring physical labour. Additionally, the underrepresentation of women at senior levels is unfortunately a problem seen in almost all countries.

Following on from the low participation rate for women, looking at the unemployment statistics has not provided many reasons to be optimistic. The unemployment rate for women has been dropping, but that fall is largely due to women leaving the labour force rather than getting employed. The extremely high unemployment for young women provides a significant deterrent for women to pursue a career at a key time in their life. Finally, women are significantly underrepresented in senior positions within the workplace. With all these factors against them, the higher number of women falling into the category of discouraged workers is completely understandable.

However, amongst the bad news were some rays of light. Women who do manage to make it into the workplace tend to be taking more technical and professional positions. As compared to the physical jobs men are more likely to take, these jobs tend to be more stable and allow for longer careers. There are also sectors where there is already a significant population of women. In a lot of ways these sectors can help provide a beachhead for women in the workplace, helping to nurture and train young career focussed women who can then move into senior positions in other sectors later in their careers.